< Back to Articles

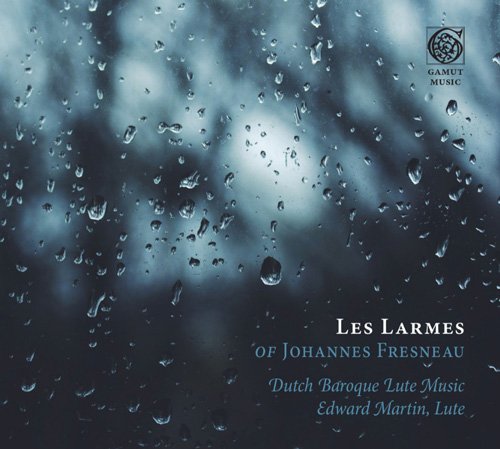

[Review] Les Larmes of Johannes Fresneau:

Dutch Baroque Lute Music – Edward Martin, Lute

By Anna F. Porcaro

This review was originally published in the Lute Society of America Quarterly 2021 - Volume 56, No. 2 & 3

As musicologists explore various archives and manuscript collections, we should continue to see lute compositions that have been forgotten over time. It was not uncommon for a lute composer’s works to exist only in manuscript form, as we know from the works of the well-known and published John Dowland.

One name that should now become familiar to lutenists and connoisseurs is Johannes Fresneau (also known as Dufresneau). Little is known about Fresneau outside of the research that has been done by Jan W. J. Burgers, who uncovered his works primarily in two sources among seven known of so far: a manuscript in the library of the Goëss family in Austria at Schloss Ebenthal (Goëss I), and the other in MS. 40626 at the Biblioteka Jagiellońska in Kraków, Poland.

Burgers has uncovered that Fresneau was possibly from Selles-en-Berry (present-day Selles-sur-Cher) in France, and moved to the Netherlands in 1637, where he was active in Leiden. In 1644 he married Annet Asseling, the daughter of one of the leading luthiers of that town. Fresneau outlived his wife and only daughter, Maria, who may have both died of the plague in the 1650s. In 1670 Fresneau’s health rapidly declined; he died and was buried in February of that same year. In the liner notes to Les Larmes of Johannes Fresneau, Burgers speculates that Fresneau was central to the lute community in Leiden and “probably taught the children of the Leiden burghers and also the young men who came from all over Europe to study at Leiden University.”

Edward Martin’s 2020 recording provides a nearly complete recording of Fresneau’s lute works (to date, we only know of thirty-three lute works and five guitar compositions). To the benefit of the lute community, Burgers’s edition of the complete works of Fresneau is available as a PDF download on the Lute Society of America’s website. Although the pieces are not always organized by key or in suites in the original manuscripts, Burgers has grouped them by key and in a way that a baroque dance suite would typically be ordered in his edition. For this album, Martin has recorded the works primarily based on ordering found in the Burgers edition.

Although written in Holland, these works sit clearly in the French-influenced style brisé and could easily be paired with other French baroque lute works by Dufaut, Gallot, the Gaultiers (Ennemond and Denis), and Mouton. Fresneau’s works are not ostensibly virtuosic, but in Martin’s hands they are full of life and emotion. Additionally, the recording engineer puts the mic close to the instrument, allowing the listener to experience what it might be like to be at a private concert sitting next to Martin and his instrument. The recording gives us the ambient and delicate sounds of movement from his fingers on the strings and frets.

One of the highlights is “Le tombeau de Fresneau” in F Sharp Minor. Its location in the recording, surrounded by the Sarabande and Chaconne in A Major, provides a welcome key contrast to those works. The melody, which contains many suspensions and deceptive resolutions, helps to create a plaintive and reflective mood that you would expect from a tombeau by Weiss or Mouton.

The chaconne is another piece that is worth repeated listening. Even at a slow tempo, the work has a lilting characteristic about it that betrays its dance underpinnings. This becomes especially evident in the second half, when the bass line repeats a chaconne pattern for the rest of the work: short-long, short-long, short-short-short, short-long. Between the repeated pattern of the second half and the overall structure of this work, Martin has plenty of room to create seamless improvisations or diminutions in the repeats, making this piece feel as if Martin were improvising the work over a chaconne bass.

One work that must be heard is the namesake of the album, “Les larmes de Fresneau” (The tears of Fresneau). On this track Martin plays the MS. 40626 version, which has a more improvisatory feel of a preludio that focuses on the broken melody and step-wise bass, than the chord-heavy version of the Goëss I version. While Martin does not improvise figuration in the repeats of this piece as he does on many other tracks, his playing leaves the listener with the impression that he is improvising. Martin takes care to allow each piece on this album to organically unfold, and by doing so he brings these unknown works by an unknown composer to life.

This album certainly makes it clear that we must add Fresneau to the repertoire as his works bear repeating. Between Burgers’s readily available scores and Martin’s premier recording, we now have a bold introduction to an important figure in Dutch lute playing, one that shows us how widespread the French style of lute playing was is western Europe even with new compositions from northern Europe.